The First May First: Haymarket, Chicago, 1886

We continue telling the history of our union's name: on May 1, 1886, tens of thousands of workers went on strike. In Chicago alone, up to 80,000 marched for the 8-hour day. Bosses responded with violence — hiring scabs and unleashing police brutality.

ENGLISH

4/16/20253 min read

In the mid-1800s, Chicago rapidly grew into a major industrial hub — the second-largest city in the U.S. at the time. New factories drew in thousands of migrants: Irish families fleeing famine, as well as Germans, Poles, Lithuanians, and others. Like many migrants today, they were trapped between two forces: exploited by bosses as cheap labor and used as a scapegoat for society's ills.

Despite efforts by the bosses to divide and control workers, Chicago’s poverty and harsh conditions made labor organizing inevitable. The city became the heart of the American trade union movement, with migrant workers playing a leading role.

The Fight for the 8-Hour Day

In 1869, a group of tailors started a secret union called the Knights of Labor. Within 15 years, it grew to 700,000 members nationwide. They campaigned for an 8-hour workday — a huge shift from the norm of 10- to 12-hour days, six days a week. They also opposed child labor and prison labor, issues that still affect workers in the U.S. today.

Another major group was the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (FOTLU), which united craft-based unions. Meanwhile in Chicago, a strong anarchist movement also emerged, centered around the German-language newspaper Arbeiter-Zeitung, edited by an activist August Spies, who would soon become a key figure.

In October 1884 a FOTLU convention taking inspiration from the stonemasons of Sydney and borrowing one of their key tactics of ultimatum declared that “eight hours shall constitute a legal day's labor, from and after May 1, 1886". Unions across the U.S. began preparing for a massive nationwide strike.

May 1, 1886: Strike Begins

On May 1, tens of thousands of workers went on strike. In Chicago alone, up to 80,000 people marched for the 8-hour day. Business owners responded with violence: hiring scabs and unleashing police brutality on strikers.

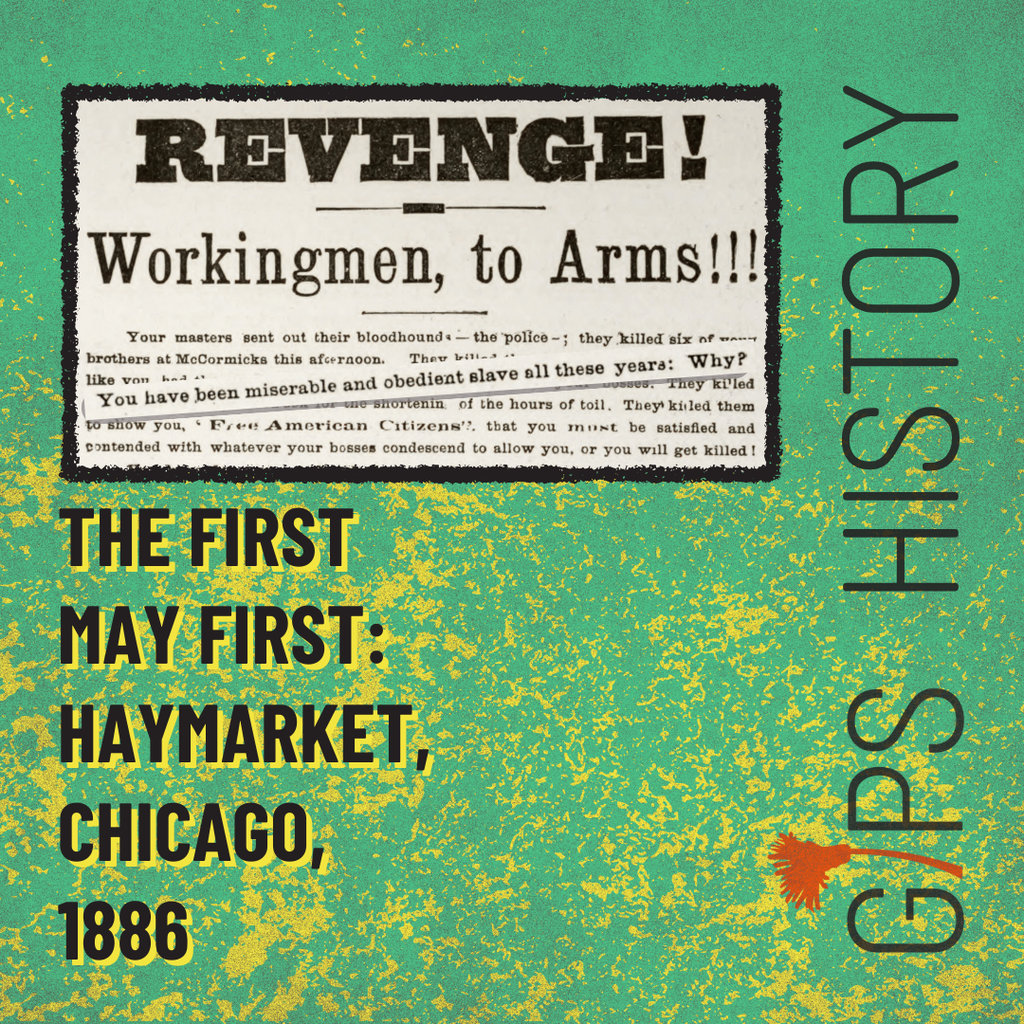

On May 3, outside an agricultural factory, police opened fire on a crowd of striking workers, killing six. Spies, who had been present on the picket line, would write “this butchering of people was done for the express purpose of defeating the eight-hour movement”.

Horrified by the slaughter, workers called a rally against police brutality the next evening at Haymarket Square. Around 3,000 people gathered in the rain to hear speeches, including one from Spies. The rally was peaceful.

Then, as police ordered the crowd to disperse, someone — to this day, no one knows who — threw a bomb. A police officer died instantly. The police responded by firing in all directions into the crowd, reloading and firing again. When the dust settled, 4 workers had been killed, though many more were injured. On the other side, 7 policemen had been killed from friendly fire or protesters desperately fighting back for their lives.

The Crackdown

A wave of repression followed. Unions were blamed for the violence, and German immigrants were targeted with racism and attacks. The bosses leaped at the opportunity to label strikers as ‘rioters’ and, as the movement subsided, took their pound of flesh in the form of victimisations and blacklisting to ensure that the 10 hour day remained enforced.

Police raided homes and offices across the city, shutting down the Arbeiter-Zeitung and arresting dozens of union leaders and anarchists — many of whom had nothing to do with the Haymarket protest.

Eight men, including Spies, were put on trial. There was no evidence linking them to the bombing. The trial was rigged from the start, with no real evidence about the actual bomber, the judge openly hostile, and the media clamouring for blood. When selecting the jury, union members and anyone with sympathy for socialism were rejected, so it took weeks to form a jury, most of whom were openly prejudiced to the defendants. All eight were convicted; seven were sentenced to death. One man killed himself in prison. Four, including Spies, were hanged. They became known as the Haymarket 7, martyrs of the labour movement.

A Global Legacy: May Day

The outrage didn’t stop at the U.S. border. In 1889, the Second Socialist International which at the time organised parties and unions across the globe declared May 1st an international day of worker solidarity — inspired by the events in Chicago. May Day was born, and in 1890, millions marched across Europe and America for the 8-hour workday.

Though U.S. unions suffered in the years after the Haymarket Affair, the struggle didn’t end. From the Battle of Blair Mountain to the impressive Minneapolis teamsters strike and the rise of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), workers kept fighting for dignity and justice.

Today, new union movements in the US are rising again — in Amazon warehouses, Starbucks stores, and railroads. As workers organize, many look back to 1886 and the Haymarket Martyrs for strength.

We, the May 1st Labour Union, are also inspired by their resolute struggle for fundamental human rights; we fight for shorter, safer and well-paid work for all.